"I

should not dare to leave my

friend"

for Double Choirs of 24 female voices, 8 flutes (2 c; alto; bass) and

2 harps based on a poem by Emily Dickinson

(a fragment from the middle of the piece

(page 7))

| pages 1 | 2

| 3 | 4 |

5 | 6 |

7 | 8 |

9 | 10 |

11 | 12 |

13 | 14 |

15 | 16 |

17 | 18 |

19 |

| listen to a

simple computer

model of I should not dare... [requires QuickTime]

| NEW: download PDF of

I should not dare . . .

(twenty-one 11' by 17" (A3) pages) [requires Acrobat

Reader ]

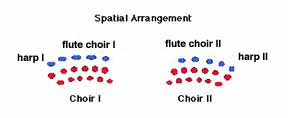

Music in Space

One of the primary features of "I should not dare to leave my

friend"...,

like its companion

pieces

Lament and Everything is...

(also for double choirs

and based on a poems by Rilke and Anna Akhmatova respectively), is the

arrangement

of the ensemble. The 24 voices are grouped together in two complementary

choirs,

each with six sopranos and six altos. The piece may be performed with or

without a

kind of background group of 2 flute choirs (2 x C; alto; bass) and two

harps. The

supporting choirs—which in turn may also be performed independently

of the voices—

play almost entirely sotto voce, which here should be taken literally

as meaning 'playing

under the voices', which creates a unique kind of composite sound or

texture.

One should imagine both of the pieces being sung in a large, resonant space:

Depending on the size and acoustics of the performance space, the flute choirs

and

harps might need to be placed in front of the singers, as well as amplified

slightly.

The dynamics of the piece are restrained throughout—always centered

around mp.

The timbre is, in contrast to the two sister pieces, Lament and

Everything is...,

generally sparse and intimate in character, with the basic trajectory of

the collective

sound being, with a few exceptions, directed inward. As an alternative to

the two flute

choirs, either as an experiment or as necessity dictates, four C trumpets

and four

B-flat trumpets may be used. (Write for the alternative muting

scenario.)

In principle, there is nothing new in this spatial approach. Some of the

compositions

within the Western classical music literature which come first to mind are,

for example,

the vocal works of Hildegard von Bingen and, more especially, the

choral music of

J.S. Bach. Consider, for example, the magnificent opening of the Bach's

Motet for

double choir, Komm, Jesu, Komm (Come,

Jesus, Come: c. 1727).

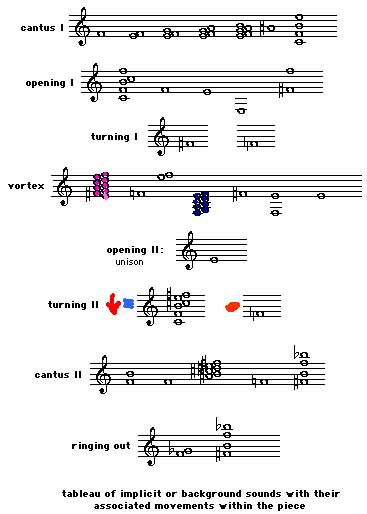

Sense, Sound and Space

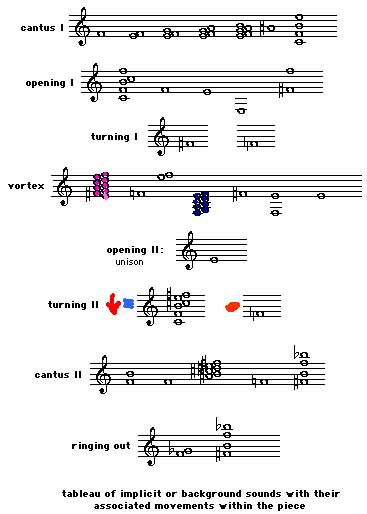

I've sketched below a rough map of what I think of as the background sound

for the whole of the piece. One might think of this as one composite sound

which

is made up of many similar, but much smaller and simpler sounds. One way

to

experience what I have in mind here is simply to have a choir sing all of

the notes

all at the same time, but very softly. Then, from this almost inaudible

background,

one would indicate for groups of voices to gradually get louder, thereby

emerging into the foreground, and then while getting softer, fold back into

the

larger, more general sound again. If one were to walk slowly through the

timbral map given below in this way, one would instantly have a sense of

how

the sound character of the music changes from moment to moment in the piece.

This little experiment would bring out three points of some significance:

(1) The character of sound, directly analogous to any kind of adjective that

comes to

mind, like sharp, or thin, or brittle, or warm, or harsh—is normally

my primary

point of departure. I don't generally think in terms of intervals, although

I

try use them with great care to obtain the quality of sound I want.

(2) The map below is just a map, that is, a highly abstract set of symbols.

The

danger of such representations is that, once we have them, the mind tends

to 'run

off' with them, as it were, and use or apply them in areas that are not

appropriate.

(Think of, for example, the maps of intelligence based on how a computer

program at present works when applied mecahnically to the mind.) What I do

in my

work is begin with the actual sound—which in my view cannot be

explained,

that is, how one actually does this; it can only be demonstrated— and

then

proceed to the mapping stage, or in the case of a performance score, the

actual

musical notation. (My central criterion as to how the music is finally

written down is essentially a negative one: avoid all unnecessary difficulty.

This tends towards a natural kind of simplicity even though the music

may still be at first difficult to perform, but then, hopefully, only because

it

is new.)

(3) Despite the limitations of the map analogy, it is still a pretty

good

one when applied to sound. This is because sound in its very most general

sense is indeed spatial, that is, it is characterized by the

co-presence of difference.

I fully realize that this sounds very theoretical if not arcane, but

actually it is not.

This way of thinking about sound is not much different then thinking about

how

you have the different items, say, a bed, a writing table, a chair, distributed

in a

room.They are all together present at the same time, which establishes

instantly

a happy or not so happy interplay of the different elements. The key point

is that time, or rhythm in music, as we experience it, is very different.

Things,

that is, difference, happen as we say—one at a time, and not all together

at once.

One of the wonderful and fascinating things in music is how time and space

in this sense refer or point or imply one another, one folding into the other

and

back again.You can experience something of this even if you do not read music

simply by playing single notes on a piano while pushing down the sustaining

pedal:

each single step of a line or journey—the separate notes—becomes

part of the

weave of the whole—a (background) chord. This is in my view exactly

what

happens also in a poem. As we hear or read the poem, we push down the

"sustaining pedal" of meaning, and hear as a kind of chord all the

different

sounds and senses resonating together. This then is how the poem and the

music are inherently very closely and intimately related. And also—at

least

this is true in my case—this is how certain qualities of musical sound

may be

felt to manifest or express the sense or quality of a poetic image.

On the map below, you can click on the notated sounds to take you to the

corresponding passage in the performance score:

The Poem

(recording)

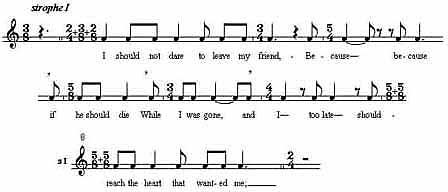

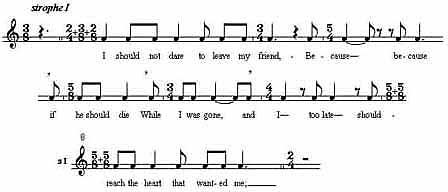

"I should not dare to leave my friend"The music follows very closely

the rhythm of the poem, using for this a new kind of composite meter

composed

of different groupings of 2's and 3's. Here's a simplified view of the first

stanza

of the Dickinson poem shown in the type of metrical notation used in the

piece

Note that, despite the tempo changes, the eighth remains constant

throughout,

with the tempo around quarter = 76 (152)):

And here is the complete four stanza text of the poem. (To view the entire

metrical

version of the same text, go to the one-page

version of the basic vocal line.)

I should not dare to leave my friend,

Because—because if he should die

While I was gone, and I—too late—

Should reach the heart that wanted me;

If I should disappoint the eyes

That hunted, hunted so, to see,

And could not bear to shut until

They "noticed" me—they noticed me;

If I should stab the patient faith

So sure I'd come—so sure I'd come

It listening, listening, went to sleep

Telling my tardy name,—

My heart would wish it broke before

Since breaking then, since breaking then,

Were useless as next morning's sun,

Where midnight frosts had lain!

Emily Dickinson

(1) Listen to a recording of Cliff Crego reading

"I

should not dare to leave my friend"

by Emily Dickinson

(2) Other recordings:

Four

Miniatures a quartet of classics by Emily

Dickinson:

Have you got a brook; Much Madness;

Glee—the great Storm is over;

Each Life

(3' 31": 341K)

| pages 1 | 2

| 3 | 4 |

5 | 6 |

7 | 8 |

9 | 10 |

11 | 12 |

13 | 14 |

15 | 16 |

17 | 18 |

19 |

| listen to a

simple computer

model of I should not dare... [requires QuickTime]

| NEW: download PDF of

I should not dare . . .

(twenty-one 11' by 17" (A3) pages) [requires Acrobat

Reader ]

| back to

Picture/Poems:

Central Display | see also the vocal score of

Lament for Double

Choir |

| go to the Cliff Crego's New Music website,

The Circle in the Square:

Central Display |

| go to

Circle/Square:

Download to download

ETFs that you can display and listen to on your own computer |

| Other websites by Cliff Crego:

picture-poems.com  Picture/Poems;

Picture/Poems;

Also: The Poetry

of Rainer Maria Rilke | Dutch poetry

r2c

Created and maintained in Northwest Ohio, USA.

(I.14.2000; updated

IX.3.2001)

Questions regarding performance

materials to

score-info@cs-music.com;

Copyright © 1999-2001 Cliff Crego All Rights

Reserved